Because most of us are involved in teaching entry level composition classes, we are, whether we acknowledge it or not, foot soldiers in the academic battle over the value of general education and its ability to instill in students transferable knowledge and skills that they can apply in numerous discipline or genre specific contexts.

I, for one, am aware of this battle every day I teach; more precisely, I can hear heavy artillery rounds exploding, both near and far, every hour before I teach one of my classes. For the last five years, I have been co-teaching special sections of George Mason University’s English 100 freshman composition classes populated with multilingual, mostly international, students whose first language is not American English. As a linguist and the designated “language specialist,” I plan, teach and grade papers with my co-instructor, a composition/rhetoric specialist from the English department. In these positions, we are fighting on foreign land: our students not only do not have English as their first language, but they also do not have experience in the American education system and the types of thinking and schema students raised in within this system acquire simply by passing through it. What is most significantly missing in our students is years of writing, and reading, practice for school, and this puts all of us, students and teachers, at the front lines of the debate over the possibility, the probability, of being able to develop general academic writing skills in a one course.

David Smit’s chapter on transfer in The End of Composition Studies (2004) starts off without providing much hope that I’m engaged in a battle worth waging:

And overwhelmingly, the evidence suggests that learners do not necessarily transfer kinds of knowledge and skills they have learned previously to new tasks. If such transfer does occur at all, it is largely unpredictable and depends on the learner’s background and experience, factors over which teachers have little control (p 119).

But directly after this depressing statement, he does allow that teachers can foster transfer of knowledge and skills to new contexts if they help their students “see the similarities between what they have learned before and what they need to do in new contexts” (p 119), and in the rest of the chapter he outlines how this can happen, reviewing other researcher’s work on transfer of writing and thinking skills. So in the end I felt better about my role as a foot solider in the trenches, but Smit’s analysis left me with little that I could employ in teaching or in validating the concept of general education as a whole, other than the vague admonition to “find ways to help novice [writers] see the similarities between what they already know and what they might apply from … previously learned knowledge to other writing tasks” (p 134). I felt like I needed to call in reinforcements; I needed my own Sergeant Stubby to keep  my moral up so that I could carry on.

my moral up so that I could carry on.

It was not Sergeant Stubby who provided me with new hope that I was engaged in a battle that had merit, but rather more recent studies of transfer that provided me with a little more specific information about how to structure my classes so as to improve the odds that my student will be able to transfer the knowledge and skills I am asking my students to use in my classes to other classes and other writing contexts. One study in particular by Linda Adler-Kassner, John Majewski and Damian Koshnick (2012), highlights the significance of threshold concepts – “specific ideas within disciplines ‘without which the learner cannot progress’.” Within composition studies, the researchers argue, there are discipline specific threshold concepts: writing is a process, writing is situated with genres and social paradigms that require a writer to pay attention to purpose, audience and context. They also argue that similar threshold concepts, or at least aver lapping threshold concepts, exist in other courses — in their study, they focus on a history course — and that the key to successful transfer is to pay attention the threshold concepts required across disciples. If instructors focus on these concepts within their classes, designing curriculum that get their student so notice them, then the likelihood that students will transfer knowledge and skills learning in one class to others.

The battle is worth waging! I am not sacrificing myself, or my students, for not! I simply have to keep our attention focused on what is significant and we will prevail.

Works Cited:

Adler-Kassner, L., Majewski, J., & Koshnick, D. (2012). The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, 26 12.

Smit, D. (2004) The End of Composition Studies. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP.

Photo Credits:

- http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/world-history/a-history-of-the-first-world-war-in-100-moments-massacre-of-the-innocents–the-day-21000-british-men-walked-bravely-to-their-deaths-9442217.html

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergeant_Stubby

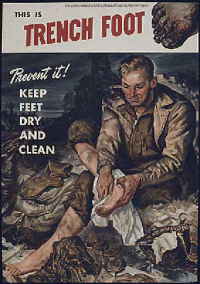

- http://www.foot-pain-explored.com/images/trench_foot_poster_200.jpg

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.